Fully automated longwall operations have been dreamt about since the 1950s. Are they finally within grasp?

by Jonathan Rowland

Longwall mining has always been associated with significant safety risks for personnel. Reducing this risk through mechanization, automation, and remote-controlled operation has – alongside improving productivity and operational efficiency – been a “central driver of longwall innovation for more than five decades,” Dr. Fiona Mavroudis, head of Application Engineering and Automation at Eickhoff Mining Technology, told Coal Trends.

This technical evolution has occurred in several stages. Early efforts focused on the mechanization of roof supports and shearers, followed by the introduction of electrohydraulic controls, which enabled more accurate operation of the face equipment. A third wave of innovation built on advances in computer technology, communications, and geospatial sensing and underground navigation systems, allowing more precise control of the cutting equipment along the seam geometry.

The earliest sensor-based automation systems were considered in the 1950s. The British National Coal Board’s Remotely Operated Longwall Face was one such early concept and “anticipated key principles of today’s mining automation,” continued Mavroudis. This included removing personnel from hazardous work areas and integrating sensor and monitoring systems. Subsequent years saw the exploration of distributed operational control systems, intended to enable coordinated and automated processes along the face. Yet, technological limitations and the harsh underground conditions meant a “fully reliable automation system could not yet be implemented,” the Eickhoff engineer concluded, and longwall mining “remained a largely manual task.”

Since the turn of the Millennium, there has been significant progress in implementing fully integrated autonomous solutions. The past decade has seen a transition from automating individual process elements to implementing the first automatic and semi-automatic longwalls, according to Karol Bartodziej, Control Systems Development director at FAMUR. These latest solutions integrate innovative control platforms, intelligent sensors, and cutting-edge communication systems to enable real-time decision making, adaptive equipment control, and a significant leap forward in operational efficiency.

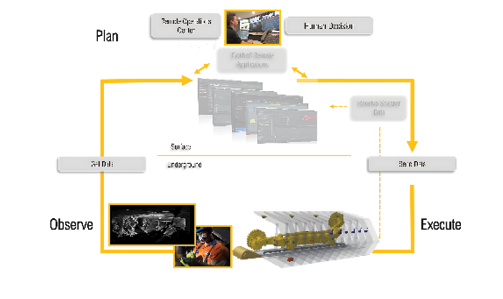

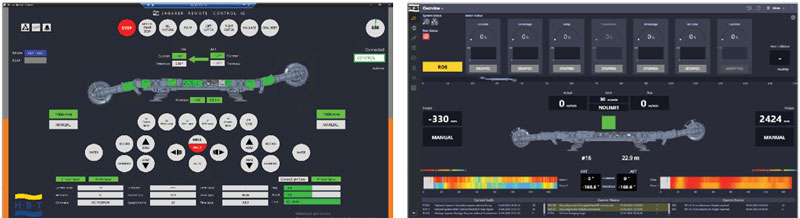

The latest milestone in longwall automation has been the implementation of remote operations from centralized surface control rooms. This represents a high-water mark of highly advanced automated mining, but it does not equate to a completely unmanned longwall face. “Longwall mining remains a human-in-the-loop process,” as Mavroudis put it, with human operators guiding operations, albeit proactively and holistically, rather than reactively. Picking up this point, Bartodziej called it “noticeable” that longwall automation still falls “significantly short of the level of automation found in production plants.”

The modern, automated longwall

Despite these caveats, the modern longwall system incorporates levels of automation that those British National Coal Board engineers could only dream about back in the 1950s. It combines several integrated elements, as Tobias Walzok, Engineering Management – Automation, at HBT GmbH, explained. At its core, a control system enables precise control of the longwall’s drives, powered roof supports, cutting systems, and armored face conveyors (AFCs), in a harmonious dance. Traditionally, this control system would have been electrohydraulic; however, the next generation of automation control systems uses microprocessor-based programmable mining controls.

The ”defining feature” of longwall automation has been the transition from manual to automatic powered roof support advance as the shearer progresses, said Eickhoff’s Mavroudis. As the roof supports advance, they push the AFC pans, eliminating manual effort for overall face advance or gate-end operation. “Even complex situations, such as turning the face, can now be handled automatically: preset distances allow roof supports to execute a wedge cut with precision.” Face alignment has also reached a high level of automation with inertial navigation technologies embedded in the shearer, providing continuous tracking, measuring straightness and horizon, managing creep, and delivering 3D information about the cutting path. This ensures consistent alignment and efficiency.

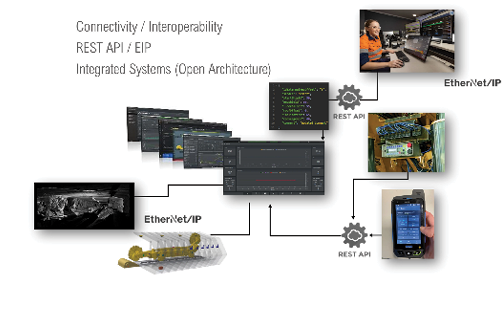

In addition to the longwall equipment itself, modern longwall automation relies on reliable supporting infrastructure.

Sensors and monitoring systems provide real-time insights into equipment condition, geotechnical stability, and environmental factors. In addition to monitoring normal operations, these support modern exception management systems, which are designed to anticipate potential failures and trigger automated countermeasures. Meanwhile, high-speed, redundant communication networks connect underground operations to surface control centers, allowing real-time data exchange and rapid data retrieval, which support centralized visualization, diagnostics, and remote operation.

Next-generation communications and sensor technologies are “revolutionizing underground mining,” said Walzok, pointing to several recent innovations, such as:

- Wireless mesh networks for reliable connectivity.

- High-resolution LIDAR and radar systems for precise mapping and positioning.

- Edge computing, bringing intelligence to the source, for real-time processing and faster response times.

Combined with IoT integration, these technologies “provide continuous monitoring, predictive insights, and a new level of situational awareness,” the HBT engineer concluded. In this brave new digital world, open interfaces and interoperability across third-party tools and customer applications are also critical to ensure flexibility and future scalability, Mavroudis added.

Enhancing productivity and worker safety

According to Walzok, automation is “redefining longwall mining productivity and safety” through optimized cutting sequences, reduced downtime, and increased equipment utilization. These directly boost output while minimizing human exposure to hazardous conditions.

One of the most pronounced benefits lies in the consistency and precision achieved during coal extraction, as noted by Eickhoff’s Mavroudis.

“Following the introduction of shearer automation, operators were encouraged to adopt a hands-off approach. Subsequent monitoring revealed a reduction in pan angle deviations, as automation minimized unnecessary swivelling movements in the floor and roof. The result was a smoother floor, more stable longwall conditions, and improved face quality. Data analyses comparing manual and automated operations illustrate the shift from operator-driven variability to consistent, high-quality outcomes.”

Meanwhile, operations that have adopted a remote mining approach report longwalls that are “consistently flat and level, with fewer blockages and reduced shield cycling times due to improved horizon control,” Mavroudis continued. Taken together, these improvements enhance production output and yield while extending the service life of equipment and consumables, such as picks, by reducing strain and damage.

Equally important are the advances in safety achieved by reducing worker exposure to dust, noise, and risks associated with machinery. This is particularly true when longwall operations have made the paradigmatic shift to remote, surface-based operation. “Automated systems provide consistent operational control, reduce equipment wear, and optimize resource recovery, while simultaneously ensuring that human operators are relocated to secure, remote environments,” concluded Mavroudis. “These advancements constitute a fundamental transition in longwall mining practices, paving the way toward safer, more efficient, and more sustainable coal production.”

Source: Eickhoff Mining Technology.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning in longwall automation

According to Bartodziej, there are two “great hopes” when it comes to AI and machine learning in longwall automation. The first lies in generative AI capable of analyzing large-scale data sets, such as historical maintenance records, and identifying opportunities for optimization. In the example of maintenance data, this could involve identifying the root cause of persistent failures and suggesting appropriate corrective actions.

Modern sensor technologies generate “vast amounts of structured data,” said Eickhoff’s Mavroudis, picking up the theme. “Machine learning methods provide powerful tools for analyzing these inputs to allow predictive maintenance, anomaly detection, and adaptive responses to variable geological settings.” At the same time, AI expands analytical capability to unstructured data sources, such as equipment manuals, programmable logic controller code, or maintenance reports, integrating them into operational decision-making processes. This ability to synthesize both structured and unstructured information “creates actionable insights that were previously inaccessible.”

Bartodziej’s second hope for AI lies in image analysis. “Mining has traditionally relied on operator observation to detect issues and keep the face running,” the FAMUR engineer explained. Efforts to replace these observations encounter various challenges, notably the substantial amount of cabling required. Modern image analysis circumvents these issues, returning to visual observations, but with inferences made in AI-supported logic and control systems, rather than in the mind of the operator. “It is a field that will undoubtedly transform the world of automation in the years to come.”

The next significant step in longwall automation lies in the development of AI systems that combine human domain knowledge with digital intelligence.

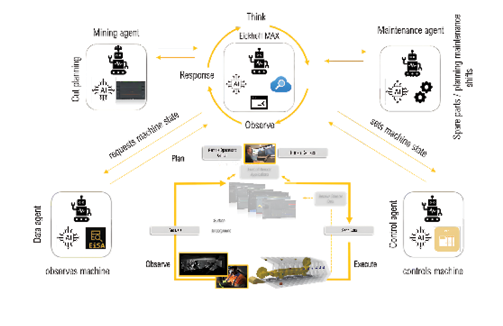

Such systems will be designed to sense, interpret, and act within operational environments, continuously learning about the face conditions and, with minimal prompting, generating solutions to specific challenges. Importantly, these AI systems will be capable of collaboration, distributing tasks among themselves to enhance responsiveness and system-level adaptability. Automation thus “evolves from static preprogrammed routines toward dynamic, networked intelligence within the mining environment.”

Parallel to this, AI is supporting remote mining operations through advanced assistance tools, such as managed assistance experts: chatbots powered by large language models can already provide step-by-step troubleshooting guidance, enable interactive diagnostics of the shearer, and incorporate OEM service expertise alongside operational documentation. According to Mavroudis, the long-term goal is to expand these systems into multi-agent frameworks, where knowledge agents, data agents, and control agents interact seamlessly to support both service and production functions. Customer-specific knowledge bases will also be integrated to ensure that AI systems adapt to the unique requirements of each mining environment.

Even with such developments, human oversight “will not disappear,” the Eickhoff engineer asserted. Instead, AI and machine learning are “redefining the human operator’s responsibilities,” from actively operating longwall machinery to validating data-driven insights and intervening when necessary. In this way, AI augments human expertise, enabling systems that are “safer, more adaptive, and better aligned with engineering judgment.”

Longwall automation limitations and challenges

Despite the notable advances in longwall automation in recent years, there remain some persistent technical and environmental hurdles that obstruct autonomous deployment. These challenges include difficulties in predicting and responding to geological conditions and phenomena, the harsh operating conditions experienced by automation hardware, the need to use intrinsically safe devices, and the number of electrical connections required to maintain reliable automated operation.

Accurately pinpointing the spatial positioning of longwall machinery is a “critical issue,” said Mavroudis. For example, AFC pan placement directly influences the shearer’s trajectory and thus the shape of the coal face. Yet generating an accurate and dependable seam model to steer the shearer “remains elusive.” According to the Eickhoff engineer, achieving genuine autonomy thus depends on seamless integration of geological maps, real-time face geology data, accurate extraction metrics, and predictive cut-planning systems; however, the current level of seam-model precision is insufficient to eliminate the need for human corrective intervention.

Similarly, seam detection is another “significant unresolved challenge,” Mavroudis continued, who explained that identifying the coal-rock interface must be achieved with high reliability under dynamically changing geological conditions. Although some emerging technologies, such as sonic steering, shield-based cameras, LiDAR, and other horizon detection systems hold promise, development of a robust solution to this challenge is “still a work in progress.” In addition, exceptions such as blockages and hazardous conditions are currently identified manually, which often requires personnel to walk alongside the shearer. “A crucial step toward higher autonomy is the development of dynamic and automatic exception-management systems that can minimize the exceptions and then address them without human involvement.”

Another issue is the difficulty in adapting devices from non-mining markets to explosive atmospheres, with the R&D period for a specific electronic device often exceeding the lifecycle of modern electronics manufacturers, explained FAMUR’s Bartodziej. This situation is exacerbated by the relatively small number of coal mining electronics manufacturers compared to consumer electronics or even traditional industrial electronics.

Aside from the intrinsically safe requirements, the harsh operating conditions found in underground mining are challenging for equipment, as Mavroudis said, noting that “technologies successful in other contexts often require substantial redesign before viability, delaying their roll-out and limiting the range of automation options.” Meanwhile, the conditions can quickly degrade the durability and reliability of advanced components. Given the number of electrical connections that must be maintained in these conditions, this is a “serious impediment to the development and durability of longwall automation systems,” agreed Bartodziej.

Automation and the human factor

There is also a human element to any rollout of automation technology, with “resistance to change a pervasive issue,” Eickhoff’s Mavroudis said, particularly among operators who fear losing jobs, even though practical experience of implementing automation has shown it often increases employment. As Bartodziej noted, “many more people are needed to diagnose and maintain automated systems, as these systems need all mechanical and electrical components to be in working order to function.”

What automation does drive is a fundamental change in the role of personnel, as operators transition from manual tasks to supervisory and technical functions, which can require comprehensive training and upskilling of existing workers. “Strong leadership and constructive industrial relations are vital to managing this transition,” said Mavroudis, “with transparent communication of objectives combined with a phased implementation strategy often facilitating workforce acceptance.”

People are “at the heart of every successful automation journey,” agreed HBT’s Walzok, noting the importance of empowering operators and technicians through hands-on training with simulators and onsite workshops, complemented by digital learning platforms and interactive remote support. “Certification programs ensure professional competence, while partnerships with mining companies and educational institutions foster collaborative learning,” added the HBT engineer. “This approach ensures that teams are fully equipped to operate and maintain advanced automated systems with confidence.”

Automation is also “not an isolated upgrade but the culmination of organizational maturity,” concluded Mavroudis. Mines that succeed in their deployment typically exhibit disciplined operations, effective maintenance practices, and reliable digital infrastructure. Attempting to automate without these foundations leads to prolonged adjustment periods and inefficiencies. In this sense, automation represents the final stage of organizational development – the “cherry on the cake – which cannot be placed until the supporting layers are properly built. Attempting to introduce automation without these risks can result in “protracted transition periods, reduced efficiency, and loss of confidence in the technology,” the Eickhoff engineer concluded.

What’s next?

The future of longwall mining is “autonomous, intelligent, and sustainable,” said Walzok, who anticipates fully autonomous longwall operations based on:

- AI-powered decision-making support systems that optimize operations in real time.

- Augmented reality interfaces that transform training and maintenance.

- Digital twins that enable predictive planning through virtual simulations.

- A focus on sustainability goals, such as energy efficiency and reducing environmental impact.

Eickhoff’s Mavroudis offered a similar vision, with automation evolving from operator-dependent systems toward autonomous, adaptive, and data-driven operations. “The vision is for fully automated longwall equipment capable of hauling and cutting across the face with no manual input, requiring operators only in supervisory roles at the surface.”

According to Mavroudis, realizing this vision depends on the development of advanced sensing and exception-handling technologies that can accurately monitor hazardous conditions, manage the horizon, and predict machine conditions and environmental hazards in the gate and face areas. These capabilities will reduce reliance on manual inspections – currently performed by operators walking alongside the shearer – and will mitigate downtime by identifying potential hazards at an earlier stage.

“This transformation will establish new benchmarks in productivity and safety and will reshape the interaction between humans, machines, organizations, and the mining environment.”

About the contributing companies

Eickhoff and the mining industry are inextricably linked. Components for underground use were among the first products of the company, which supplied Europe‘s first bar coal cutter in 1914. Whether at one of the world‘s most productive mines in the Southern Hemisphere or the world’s biggest shearer loader in Inner Mongolia, Eickhoff mining machines are at the forefront. Eickhoff shearer loaders and continuous miners steadily set new standards of quality and innovation.

FAMUR delivers advanced and efficient automated longwall systems, as well as transport and reloading systems for moving various materials and personnel underground. It also offers systems for monitoring machine operations and enhancing the safety and efficiency of the mining process. Years in the mining industry enable FAMUR to design and manufacture machine systems adapted to challenging conditions.

HBT is a machine manufacturer and a fully integrated, single-solution provider, specialising in systems and equipment for underground coal mining. The company exports its high-performance longwall mining equipment to all major mining markets worldwide. From low seams to high seams, regardless of the face length or production demand. HBT understands the challenges faced by longwall mines today and has developed its equipment to meet those demands.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Dr. Fiona Mavroudis would like to acknowledge Anglo American Australia and Glencore Australia for providing material and inspiration for some of the figures included in this article.

The first forays into longwall automation began in the 1950s, including Eickhoff’s seam boundary detection system and the British National Coal Board’s Remotely Operated Longwall Face concept. Image: Eickhoff Mining Technology.